In Kenya, the fear of assault grows by the minute. The numers in Nairobi don’t lie, and each case represents a real person.

Yet the response to SGBV remains inadequate. Is this society accepting it as the norm, or is the reality too harsh to fathom?

A widely accepted culture continues to normalise the violence, raising the grim prospect that we could be heading down a path similar to India’s.

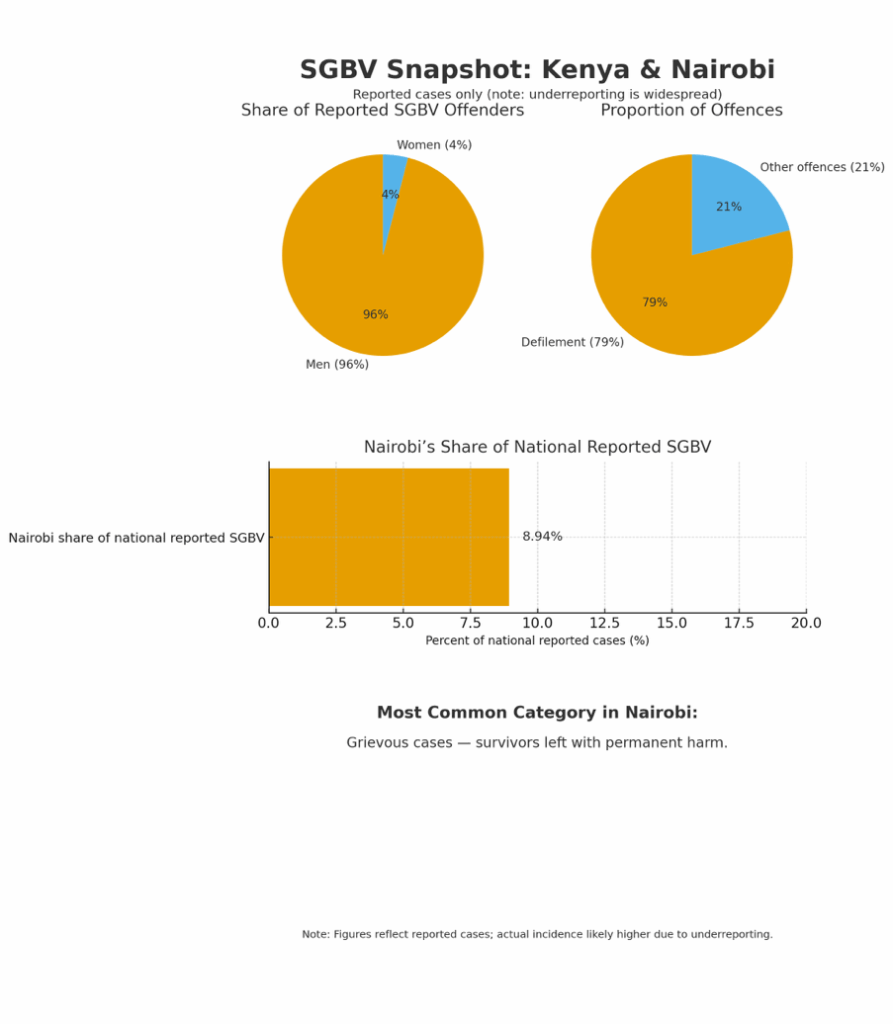

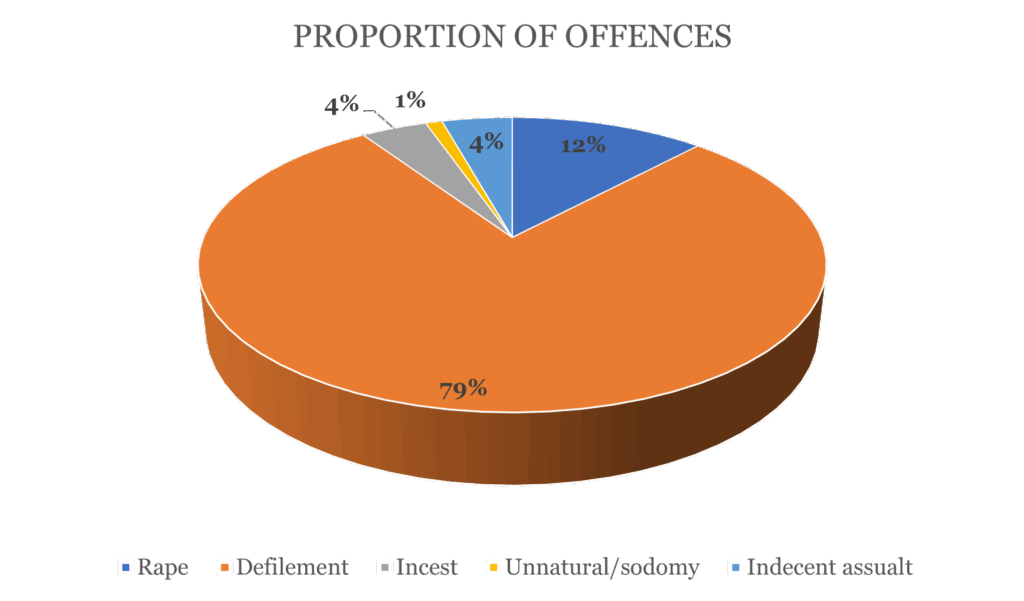

National data show a hard truth: men commit 96% of reported SGBV offences. Defilement accounts for 79% of cases. In Nairobi—home to 8.94% of the country’s reported SGBV—the most common category is “grievous”: survivors left with permanent harm. Add the reality we all know but rarely state plainly—underreporting is rife.

Kamukunji is in the middle of this crisis. A constituency with a proud history of civic struggle and a significant informal economy. It is also a place where poverty, overcrowding, insecurity and the thin social protection amounts the risks of safety.

According to our analysis, Nairobi bears the heaviest documented burden of Sexual and Gender Based Violence. Kamukunji is not an exception. The risks here mirror the city’s trends, and the unfortunate part is the lack of localised tools to prevent, respond and heal.

This is not inevitable. It’s a policy choice.

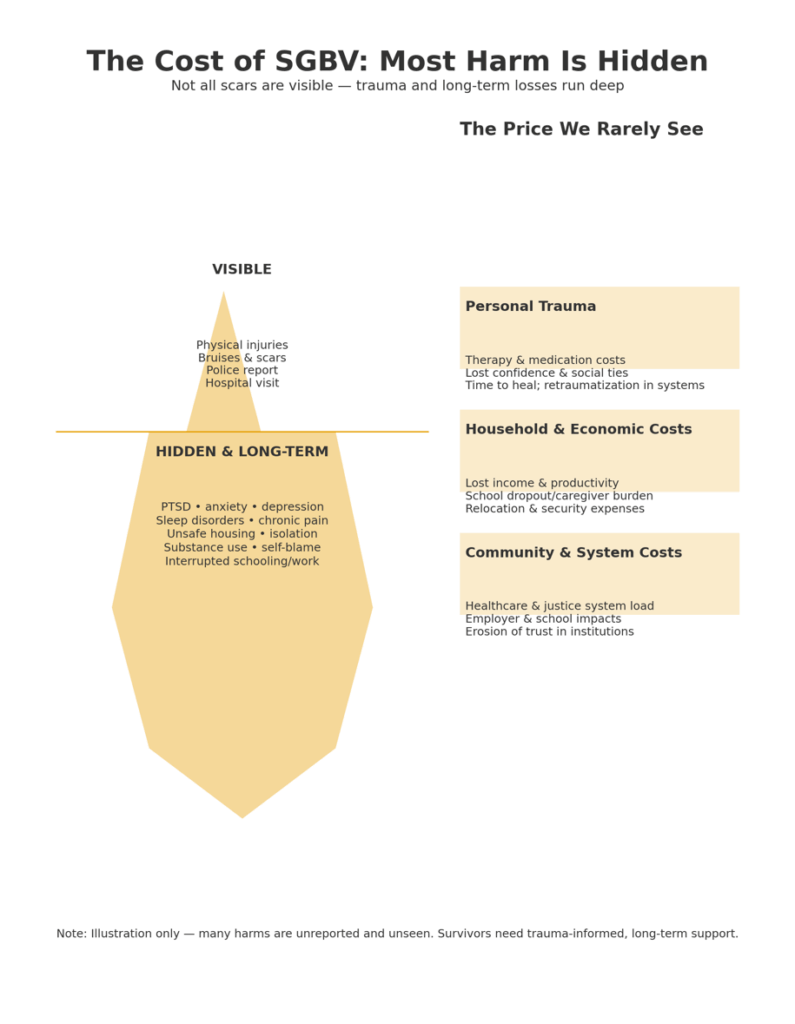

The price of SGBV is coslty. It may not be written on the physical, but the amount of trauma a survivor ednures is not anything anyone would ever imagine for their worst enemy.

Start with the obvious: children and adolescents are in danger. If defilement dominates nationally, school-centred prevention in Kamukunji must move from “nice to have” to non-negotiable.

That means age-appropriate consent and rights education, trained focal teachers, and safe reporting channels that bypass fear of retaliation. Faith institutions and parents are not afterthoughts; they are frontline partners in keeping children safe.

Survivor care must be practical, close, and fast. The prevalence of grievous cases in Nairobi tells us survivors are showing up late, or not at all, or being shuffled between services until the trail goes cold.

Kamukunji needs survivor-centred “one-stop” days rotating through local health facilities—clinical care (including emergency contraception and PEP), psychosocial first aid, legal guidance, and case follow-up—delivered together, with privacy and dignity. Justice must not become a second assault.

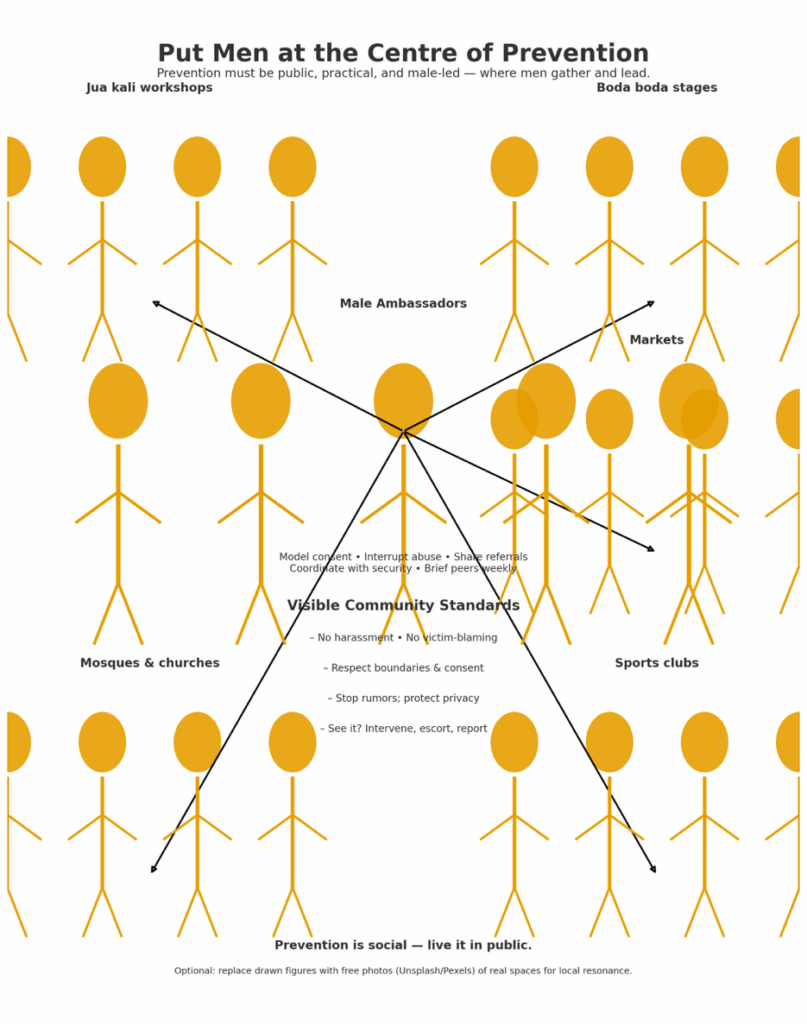

Prevention must also put men at the centre—because the data do. When nearly all offenders are male, generic awareness campaigns will not cut it. The work has to happen where men gather and lead: jua kali associations, boda boda stages, markets, mosques and churches, sports clubs.

We must have male ambassadors and set visible community standards that reject victim-blaming and normalized harassment. Prevention is social, not abstract; it must be lived in public.

Protection is also a design problem. People are harmed in specific places at specific times. Ward-level safety maps, created with residents, can identify hot spots—alleys, poorly lit paths, isolated sanitation blocks, unsafe commuter routes.

We must demnd for these fixes. They may not be glamaourous, but are obligations for secure common areas. Urban planning is a protection tool when it listens to those who use the streets.

The reporting of cases has been an issue in Kenya,and must be rebuilt with survivors. Underreporting is not only fear; it is friction. Survivors should not have to recount trauma multiple times to multiple offices. We have to straemline the pathway from first disclosure to services and evidence capture.

In Kamukunji, law enforcement, health facilities, child protection units, social workers, and community organisations smust collaborate, because when agencies don’t talk, perpetrators don’t stop.

Kamukunji has never been passive in the face of injustice. The constituency that helped bend Kenya toward democracy can also bend its streets toward safety. The data tell us where the pain is; our choices will decide whether that pain is prolonged or healed.

We owe our children more than a statistic. We owe them a neighbourhood where walking home isn’t a gamble, where classrooms are sanctuaries, and where the lion’s roar is the sound of a community refusing to look away.

By KCEI Team